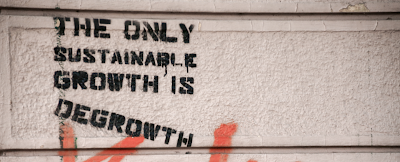

Decrecimiento o barbarie

En su ponencia para las jornadas “Otra economía está en marcha” de 2020, Jason Hickle apuntó correctamente que deberíamos replantearnos el término “antropoceno” para describir la era actual y usar en vez el término “capitaloceno.” El motivo de este matiz es que el término antropoceno, aunque resalta la importancia de la actividad humana en la situación actual del planeta, no señala que no es simplemente la actividad humana la que ha creado los problemas actuales de colapso ecológico, sino la actividad humana bajo un sistema económico particular: el capitalismo. Yendo aun más allá, Hickle señalaba que, dentro de este sistema económico global, no todos los estados tienen la misma culpa, ya que son los estados ricos los que han causado la mayor parte del exceso de emisiones global, con el Norte Global causando el 92% de las emisiones de CO2 históricas. Mientras tanto, el Sue Global sufre el 90% de los costes y el 98% de las muertes derivadas del colapso ecológico. Este proc...