Did Germany follow older colonial traditions in destroying the Nama and Herero in South-West Africa?

Although the Sonderweg* ('special path') tradition of German history has tended to overplay the uniqueness of German military-institutional culture when explaining colonial massacres such as that of the Herero and Nama in today's Namibia, Germany was part of a broader international system of colonial warfare that included international norms, principles of foreign domination, political narratives and concepts without which administrative massacres such as that of the Herero and Nama would not have been possible.

German claims to South-West Africa were formally confirmed by European powers in the Conference of Berlin (1884-5), the infamous 'scramble for Africa.' The Herero and Nama massacres would not start until a few years later, but the unlawful occupation of a foreign territory by Germany can only be understood in this broader framework of European imperialism in the first place. What has been sometimes called the age of 'New Imperialism' followed somewhat contradictory narratives of the Enlightenment, with its civilizing mission attached, and the nation-state, which following social-Darwinist ideas of the time required necessary expansion to dominate the world order and promote its own master race. These political narratives were complemented by a broader international system of European colonial warfare in which war was seen as an acceptable tool of politics and national sovereignty (of European states) as inviolable. As a 'laboratory of modernity,' as worded by Hannah Arendt, colonialism allowed the space for European powers to develop and attempt new forms of power management. Thus, new principles of foreign domination based on race as a substitute for the nation (esp. in South Africa) and bureaucracy as a substitute for government (esp. in Egypt) were being tried by European powers and were available for any other European nation-state to borrow from and implement in their colonies.

Two of the most important colonial concepts which in some form can be traced back to the origins of European colonialism and which significantly influenced the German extermination of Herero and Nama peoples are those of race and space, as developed by Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism. Although the biological, social Darwinist racism of European imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a somewhat recent development, the binary encoding of the world that denied the enemy equal status and could potentially derive in genocide and which can be traced back to Columbus was readily available to the Germans in South-West Africa, as developed by German imperialist intellectuals such as Eugen Fischer or Friedrich Ratzel. The German domestic ignorance of the colony led the German people to believe pretty much anything that was reported from the colonies, and helped frame the entire Herero and then Nama peoples as enemies to the German nation, paving the way for potential atrocities to take place. The connection of racial superiority also made tactical retreat unacceptable, especially after the arrival of general Lothar von Trotha to supreme command and with the imposition of martial law.

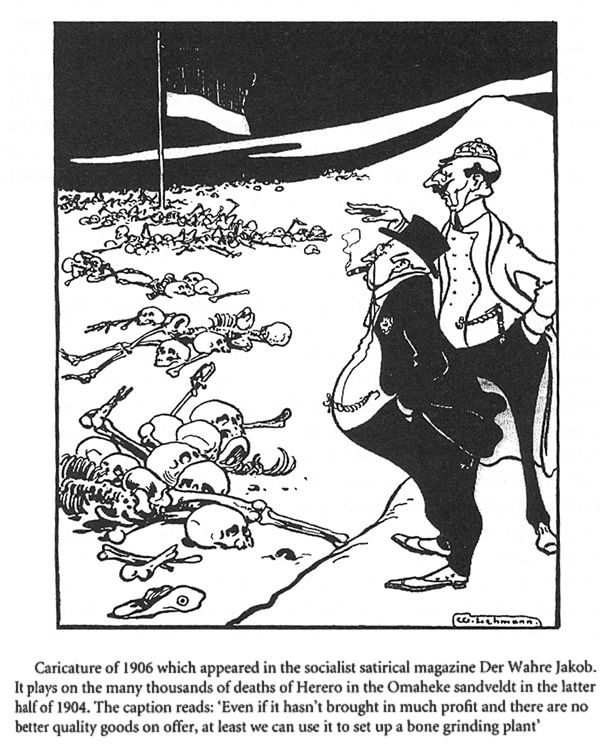

In terms of theories of space, Germany in South-West Africa combined the old colonial notion of the colonial space as a tabula rasa, a blank slate which justified occupation, settlement and control over nature (read:natives), with ideas of Lebensraum as developed by the abovementioned Ratzel. The primitive accumulation and confiscation of property necessary for the colony to 'work,' required on some occasions 'administrative massacres' such as that committed by the Germans in South-West Africa, which combined modern racism with mass killing. The 'unexpected' resistance from natives and the often unacknowledged military incompetence of European armies in colonial setting recurrently led to mass violence and murder, the toxic result of a mix between an 'efficiency-driven' governmentality and a racist and self-righteous ideology. Thus, although recognising the peculiarities of each colonizer state and colonized peoples, and in the case of Germany in South-West Africa the independence of the German military from parliamentary control or domestic scrutiny at home and the position of absolute defencelessness of the Herero, in particular after the battle of Waterberg, Germany did follow older colonial traditions in destroying the Nama and the Herero, and indeed without those older and widespread colonial ways of thinking, not only extermination but even conquest in the first place would not have been possible.

A last point of clarification, and another colonial avenue taken by Germany in South-West Africa, is that of local collaboration in massacres, conventionally regarded as incompatible with the notion of genocide (which can itself sometimes be too restrictive in recognising agency). The Nama and the Herero were not homogeneous groups equally and simultaneously 'destroyed' by the Germans, but in fact Germany played the classic colonial trick of divide-and-rule, and indeed some of the Nama people collaborated to different degrees in the extermination of the Herero. The old tradition of colonialism as a system of collaboration was again followed by the Germans, proving both that the colonized are not an homogeneous group and that, although the coloniser were not homogeneous either, Germany recurred to age-old practices of colonialism and European foreign domination.

*Sonderweg: theory in German historiography that considers the German-speaking lands or the country of Germany itself to have followed a course from aristocracy to democracy unlike any other country in Europe.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario