What did France try to achieve in Algeria?

|

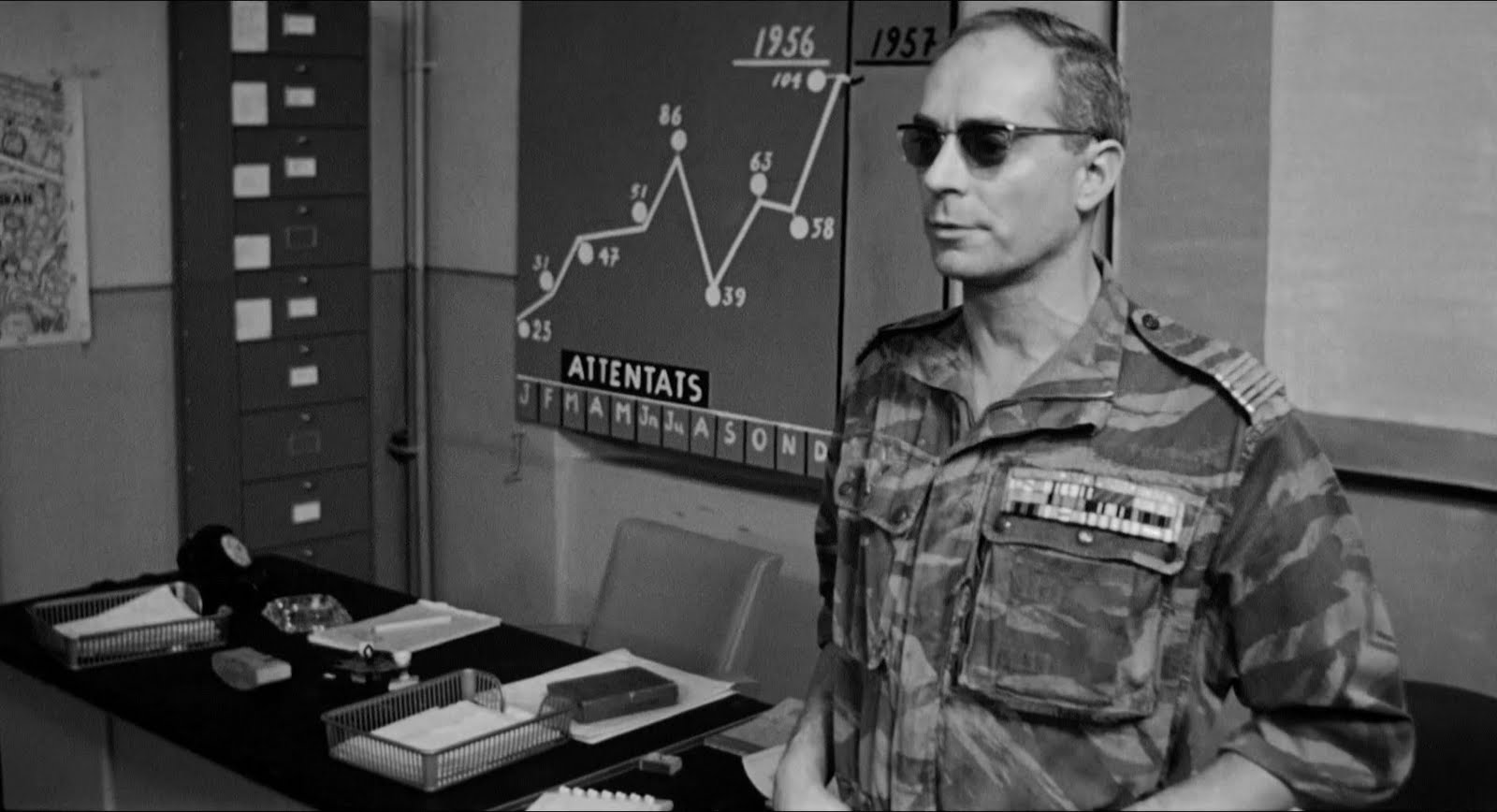

| A shot from Battle of Algiers |

With the rise of modernization theory in the American social sciences during the 1950s, the French saw an important body of knowledge that fitted with their previous mission civilisatrice rhetoric and which could help with the 'hearts and minds' of the Algerian population while keeping the insurgency of the FLN and others at bay. Counterrevolutionary counter-insurgency, as later articulated by French officer David Galula ('the Clausewitz of counterinsurgency'), was the French response to the 'revolutionary warfare' of insurgent anticolonial groups such as the Algerian Front de Liberation National (FLN), which in turn represented new postwar generation that had acquired some knowledge of Marxist revolutionary techniques and was impatient with interminable political dialogues, meaningless manifestos and unfulfilled promises by the French. This new 'people-centred counterinsurgency' aimed to get the support of the Algerian population rather than the mere control of the territory, and helped connect visions of a global Cold War with local dynamics of declining colonialism under the overall narrative of modernization. It was the idea of a transition from 'tradition' to 'modernity' and the existence of a global communist threat (more imagined than real in many cases) which integrated into one explanatory framework (modernization theory) for political unrest in the European colonies after 1945. This new patterns of colonial legitimization came together with the establishment of colonial 'emergency rule' and the negation of the validity of international humanitarian law in the colonies, which were seen as 'internal affairs' of the European powers.

With this in mind, the French administration deployed several 'forced modernization' programmes in Algeria such as the rural development programme, which attempted forced relocation into strategic villages and affected up to 2.5 million Algerians. Being part of a 'global paradigm' that could be traced back to the concentration camps of the early 1900s or to contemporary experiments by the British in Malaya and Kenya and the French in Vietnam, resettlement combined socioeconomic development with military strategy, as the implementation of socio-economic reforms in such a short time-span and to such an extent required the instruments of power of military force. The programme was initially undertaken according to military and strategic considerations alone, leading to chaos, malnutrition, and disease, triggering a humanitarian crisis and driving the native Algerian population into dependency on aid. The formation of around a thousand strategic villages (most still in existence today) led to irreversible changes in the rural settlement and economic structure, and meant the end of small-holder farming. These 'new villages' became both disciplinary spaces of control and repression and laboratories of social transformation and 'accelerated modernization,' becoming what Fabian Klose has called the 'spatialization of the colonial state of emergency,' Planning and construction of the villages required a new development industry, not unlike today's, and the operationalization of the social sciences, requiring detailed knowledge about the civilian population. For the French, the objectives of resettlement were not merely to 'develop' the Algerian countryside and its inhabitants by changing the structures of land ownership and of labour in the agricultural system, but also to break the ties between armed groups and rural civilians, and to create local militias that could fight the FLN in rural areas (often resulting in inter-communal frictions that persisted after the end of the war). Social planning was thus seen as important as fire power and tactical innovations in winning the war, and ironically led to most of the civilian deaths in the Algerian war.

Social planning was combined with economic planning, or what was seen at the time as the 'transformation of man.' Through influential units such as the Fifth Bureau, French researchers drew from social psychology to inform development policies in Algeria, transforming older understandings of social classification through a new language of aptitudes and behaviour that defined racial difference according not to biological features but to economic capacities, and based on opinion polls and psychometric tests. French attempts at economic planning were made obvious in the 1958 Constantine Plan, which showed the intimate link between social planning and the postwar social sciences characteristic of the Cold War. Its aim was, similarly to the strategic resettlement programme, to make Muslim Algerians 'compatible' with European integration, going from 'homo islamicus' to 'homo economicus' as phrased by the director of the Constantine Plan, Jean Vibert. The plan aimed to foster consumption in order to break the subsistence economy through powerful media (radio) and advertising (travelling fairs), seeing man as a consumer of both information and goods. Breaking with its predecessors, it defined development as a means of effecting a total transformation of the Algerian population. Moreover, the increasingly anti-colonial climate of the 1950s and 1960s required considerable propagandistic efforts from the colonial military to a critical global audience. As a result, planners in Algeria often seemed more concerned with the image of the Plan than with the concrete effects of development initiatives. The positive results of the plan in development terms were therefore doubtful, and even militarily they did not achieve the ultimate French aim of winning the Algerian War.

The 'transformation of man' envisaged by the Constantine Plan was not however possible without penetrating into the Muslim family, seen by the French as a bastion of resistance and simultaneously as an entry point into Algerian society. Good and accurate intelligence was crucially dependent on building close contacts with informants and local populations in general and women in particular. Despite supporting patriarchal structures of the extended family group and consistently ignoring or regarding with suspicion Algerian women's demands for political participation before the war, after 1956 the French seem to have taken an U-turn and adopted an 'emancipatory mission' that aimed at 'liberating' and 'modernizing' Algerian women, as eloquently described in Neil MacMaster's Burning the Veil (despite his somewhat problematic portrayal of Algerian women, who are not given much voice in the book). The centrality of the veil as a readily identifiable system for the policing of society led to mass unveiling ceremonies being organised by the French, often by organisations leaded by the wives of high-ranking French officers. This 'Kemalist' approach to modernization was based on a narrow view of women based on the role of women in French society at the time, where women were relegated to the domestic sphere and still very much constrained by patriarchal structures of marriage, divorce and birth-control laws. This model of womanhood was presented by the French as more 'modern' and culturally superior, and promoted among Algerian women. Moreover, the claimed French liberation was often contradicted by the violence inflicted on women through rape, torture and destruction of villages. Similarly to resettlement programmes or economic planning, the promotion of female 'emancipation' by the French followed a dual reformist and repressive purpose, with the overall aim of intelligence gathering and of winning the hearts and minds in a war of world opinion which they would ultimately lose, as the FLN was in many ways much more capable not only of waging a diplomatic war (with the help of other Arab countries), but also of creating an Algerian subject that saw him/herself as independent from France.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario